Model-to-Data PETs

Contents

Model-to-Data PETs#

Another branch of PETs is directly aimed at creating an infrastructure of actors that aim to utilize the value of the combination of their respective data. In this branch of PETs, the data is not shared into a single large dataset or data lake upon which models can be trained but the models are sent to the data. Two types of these model-to-data PETs will be discussed here: Federated Learning (FL) and Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC). Both are PETs aimed at generating machine learning models. Although some of the architecture of their implementation can be relatively similar, they are distinct, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses that dictate the appropriate application for each.

Federated Learning#

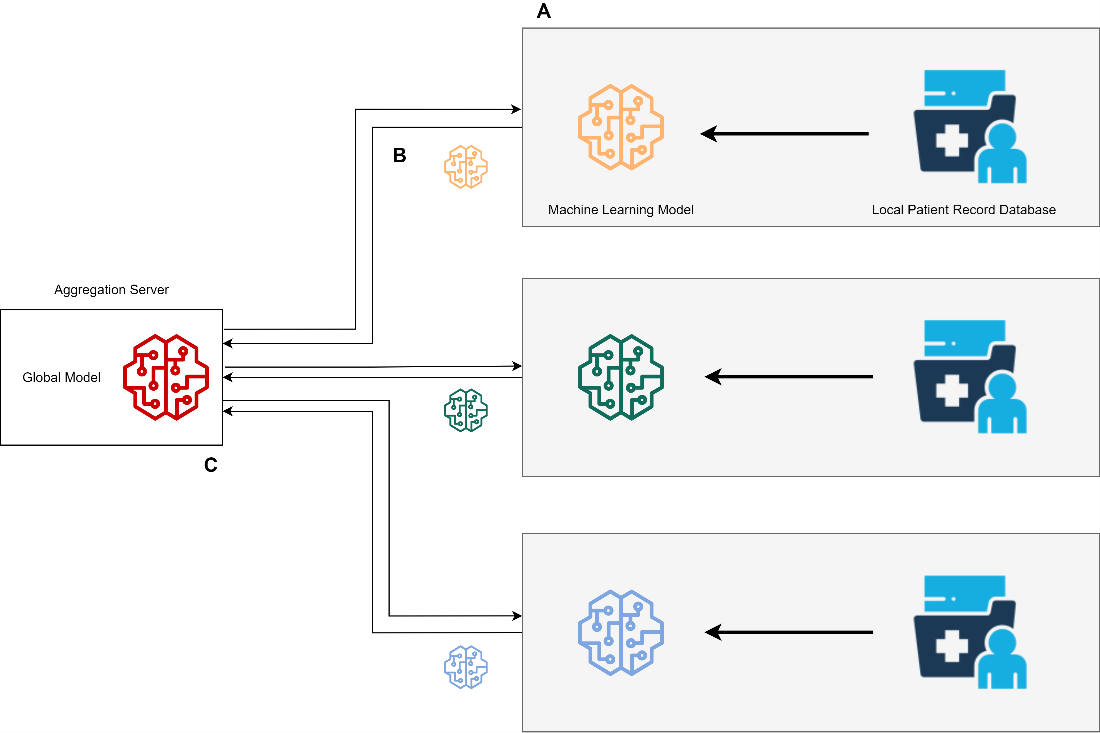

Federated Learning can be most simply thought of as model sharing. By sending models to the various data sources, we can train and update machine learning models without having to ever communicate the raw, private data. This communication of the models however does require a central authority (a server) to actually send the models, as well as aggregate the results after the model update steps.

Fig. 9 Federated Learning.#

Before going into detail of Federated Learning, we need to go into the difference between vertically and horizontally partitioned data. In any data sharing ecosystem, data can be split up in two different ways (or both). When data is horizontally partitioned, it means that two databases have the same type of data (features, variables, measurements, etc.) but different records of those features. An example could be two banks. Both have account information of their clients (such as balance sheet and contact information) but they have different clients in their systems. In the case of vertically partitioned data, two databases have different information for the same entity. An example of this would be that your dental records are stored in the database of the dentist and your prescribed drugs are stored in the database of your pharmacy. They share some information to enable linking the data (such as your name and birthday) but otherwise contain unique information about you. FL has a number of advantages for a health data ecosystem. In the simplest implementations (Horizontal FL: where data is split on records), communication is only required to and from the central authority. Other, more complex implementations of FL exist, that allow for models to be trained on vertically partitioned data (data split on column features).

Implementations

There are a number of public libraries available for implementation in a wide range of languages, such as Romanini, Daniele, et al. “Pyvertical: A vertical federated learning framework for multi-headed split.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.00489 (2021) and Tensorflow. Many commercial implementations of FL exist as well, such as those offered by IBM, NetApp, Sherpa.AI, Google and many more.

Due to the large number of mature implementations, FL is relatively simple to use. An additional advantage is the low communication overhead compared to other distributed privacy preserving techniques, as the only communication that is required is directly from and to the central authority, communication overhead is significantly lower than computational overhead for all but the most simple models. In addition, FL has a straightforward governance structure. Due to the requirement of a central authority (server) that must be trusted, data access rules and logging are trivial to implement. FL works with most machine learning models. Although there are types of machine learning models that are not suitable for training from a ‘warm start’ (i.e., models that can only be trained completely all at once), FL is suitable for essentially all other models.

Federated Learning also has some drawbacks. For starters, it is not completely trustless. A trusted central authority (server) is required to send and aggregate models. It is also susceptible to sophisticated malicious actors. Adversarial actors are capable of creating sophisticated attacks that can compromise the global model, and may be extremely difficult and computationally expensive to detect1. Models often require additional privacy preserving algorithm. Malicious actors can abuse model updates to learn about specific data points of others. This necessitates the addition of further privacy preserving algorithms, usually those that include noise into model updates (e.g.: differential privacy)2. Another drawback is concerned with small datasets. Depending on specifics of application (dimensionality of data, number of records, data bias…) there is a practical limit to how small a group of datasets should be to ensure private information is not leaked during model updates. Finally, local bias may hamper model accuracy. Although there are techniques for dealing with bias within a federated learning implementation. There are limits to the degree of bias these algorithms can mitigate 3.

Secure Multiparty Computation#

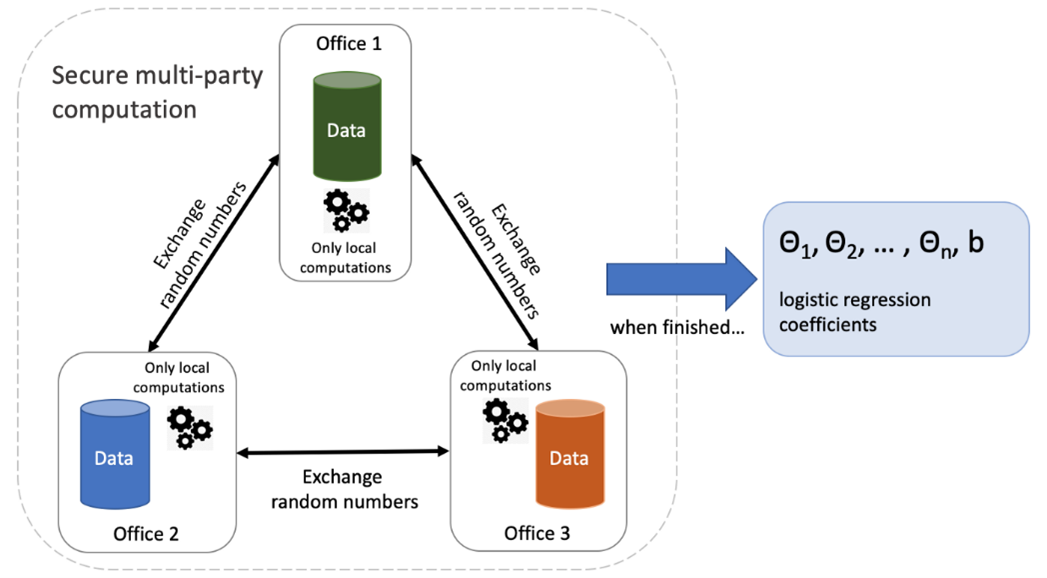

A second architectural PET is called secure Multiparty Computation (MPC). MPC is a collection of techniques that allow individual parties to calculate a function in collaboration, without the need to share the raw data. This is achieved through one or a combination of homomorphic encryption (encryption that allows for computations to be performed on the encrypted data) and secret sharing (communicating incomplete data). MPC is unique amongst privacy preserving methods for model creation due to the fact that data privacy is mathematically guaranteed up to a limited number of coordinated malicious parties ( parties within the network who attempt to compromise secret information). The most prominent drawbacks to MPC is the communication overhead, which severely limits the number of participants that may be present for a reasonable computation time.

Fig. 10 Secure Multiparty Computation.#

The advantages for MPC are as follows. Required minimum of the level of data privacy can be mathematically guaranteed. There is no minimum number of parties required and theoretically no maximum either. And finally, the models are trustless (models on encrypted data). A major drawback of MPC is the high communication overhead in respect with the typical data transfer. It happens because the cryptography used for security, by itself generates quite a lot of data which should be transferred together with the actual data being shared. This communication overhead grows exponentially with the number of parties involved, this means that there is a practical limit to the number of parties that can be involved (depending application needed for the ecosystem). Additionally, there is limited ability to use sophisticated machine learning models. Although there is active research on the topic of applying more sophisticated models using SMPC, widescale implementations in public available libraries are lacking. Finally, the governance is more complex. One needs either a central authority in the network or a decentralized system (such as blockchain) to provide governance structure needed.

Implementations

Open source implementations are developed by TNO together with academic institutes in collaboration with business and SMEs. Results can be found on Github and PyPI. Commercial implementations of this exist, such as LinkSight (a TNO spinout) and Roseman labs in the Netherlands.

Concluding remarks#

It is clear from the short list of pros and cons that privacy by design implementations of data sharing follow the principle of ‘no free lunch’, that is, there are trade-offs to any solution. What is most important when choosing the implementation is that it is fit for purpose. Depending on the utility, sensitivity and privacy requirements, one needs to choose a fitting solution.

- 1

Tolpegin, Vale, et al. “Data poisoning attacks against federated learning systems.” European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer, Cham, 2020.]

- 2

Melis, Luca, et al. “Exploiting unintended feature leakage in collaborative learning.” 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2019

- 3

Abay, Annie, et al. “Mitigating bias in federated learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.02447 (2020).